One can read the moral and social reform programme of 19-18 as preparing for a restoration of Roman social, religious and political values. Such laws are ideological in that they relate to a political view of what Rome is or should be. They were not technical, that is a means of making Rome work better. They reflect a desire for renewal.

Neither the desire for renewal nor the ideology was limited to Rome’s political leaders. It is a theme of, for instance, Horace’s Odes, particularly book III. It is even more obvious in Virgil’s Aeneid.

These are complicated works and both poets wrote generally favourable accounts of Augustus and his regime. Yet, they cannot be understood as the propagation of the ideology of the regime. Still less can we can apply the modern term ‘propaganda’ to these works.

Poets and Patrons

There was an established Greek tradition of poets writing in praise of their patrons that went back into the archaic period. Poets appear to have been dependent on their patrons. The motif of the patron was also a feature of Roman poetry, but Romans were uncomfortable with the dependence of free persons on other free persons: it looked like slavery. Many of our major late Republican and Roman poets appear to have been persons of some wealth, though none were from the highest echelons of Roman society: Catullus, Tibullus, Ovid, and probably Propertius appear to have been comfortably wealthy. Horace and Virgil may have needed and indeed benefited from greater levels of patronal support. But the role of the patron was also social. A patron made introductions and created associations. For the patron, having the learned presence of the poet was a means of showing his own cultivation .

The relationship was delicate. A patron could not demand of a poet that he produce a poem to order, as Cicero found when he unsuccessfully sought someone to write a poem in praise of his actions in the suppression of the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 BC. Indeed, a standard poetic form developed, the recusatio, in which the poet refused to write what the patron asked. The form was proclamation of friendship, but independence in that friendship.

Recusatio provided the poet with an opportunity to fulfil in part the requirements of the patron. If you talk to any writer, they’ll tell you how inventive they are in finding reasons not to write. Take this example from Propertius’ poem to Maecenas that opens his second collection (Poetry in Translation, Propertius 2.1: with the notes from the original site)

You ask where the passion comes from I write so much about, and this book, so gentle on the tongue. Neither Apollo nor Calliope sang them to me. The girl herself fires my wit.

If you would have her move in a gleam of Cos, this whole book will be Coan silk: if ever I saw straying hair cloud her forehead, she joys to walk, pride in her worshipped tresses: or if ivory fingers draw songs from the lyre, I marvel what fingering sweeps the strings: or if she closes eyelids, calling on sleep, I come to a thousand reasons for verse: or if naked she wrestles me, free of our clothes, then in truth we make whole Iliads: whatever she does or says, a great tale’s born from nothing.

Maecenas, even if fate had given me the strength to lead crowds of heroes to war, I’d not sing Titans; Ossa on Olympus, with Pelion a road to Heaven; or ancient Thebes; or Troy that made Homer’s name; or split seas meeting at Xerxes’s order; Remus’s first kingdom, or the spirit of proud Carthage, or the Germanthreat and Marius’s service. I’d remember the wars of your Caesar, his doings, and you, under mighty Caesar, my next concern.

As often as I sang Mutina; Philippi, the citizens graveyard; the sea-fights in that Sicilian rout; the ruined Etruscan fires of the former race; Ptolemy’s Pharos, its captive shore; or sang of Egypt and Nile, when crippled, in mourning, he ran through the city, with seven imprisoned streams; or the necks of kings hung round with golden chains; or Actium’s prows on the Sacred Way; my Muse would always weave you into those wars, mind loyal at making or breaking peace.

Achilles gave witness of a friend’s love to the gods, Theseus to the shades, one that of Patroclus, son of Menoetius, the other of Pirithous, Ixion’s son. But Callimachus’s frail chest could not thunder out Jupiter’s struggle with the giant Enceladus, over the Phlegrean Plain, nor have I the strength of mind to carve Caesar’s line, back to Phrygian forebears, in hard enough verse.

The sailor talks of breezes: the ploughman, of oxen: the soldier counts wounds, the shepherd counts his sheep: I in my turn count sinuous flailings in narrowest beds: let every man spend the day where he can, in his art. Glorious to die in love: a further glory, if it’s given, to us, to love only once: O may I enjoy my love alone!

The poem is an implicit refusal to a supposed patron to write about matters military. His topic will always be love. The poem poses as an answer in conversation that starts by Maecenas asking, ‘Propertius, why don’t you write about stuff other love?’

Epic and Praise

For Romans, the form of poetry most suited to praise was epic. Epic dealt with issues of great historical importance, with heroes, monsters and gods and battles that shaped consciousnesses and cultures. The great Roman hero was a man of politics and battle, a man of epic.

Our views of ancient epic are somewhat skewed by what has come down to us from antiquity. When we think of epic, we tend to think of the great ‘mythological’ epics: Homer and Virgil, stories of gods, monsters and remote foundation myths.

But the Romans also had historical epics which were based on real historical events.

- Ennius wrote an Annales which survives only in fragments, but appears to be a poetic history of Rome.

- Naevius wrote an epic version of the Punic War, which survives in the briefest of fragments.

- Lucan was to write an epic of the Civil War between Pompey and Caesar.

- Silius Italicus composed the Punica, an epic on the Second Punic War.

It would, thus, have been possible for a poet to write an epic on a contemporary historical theme, but when Virgil came to write the epic of the Augustan age, he chose a mythological form: the Aeneid is not the story of Augustus nor the story of contemporary Rome, but of the mythological foundation of the Roman people. It does of course deal with contemporary themes: fate, leadership, respect for the gods, love, duty, Roman values, masculine values, community, violence and civil war. It is filled with discussions of contemporary ideological values and makes frequent and explicit reference to contemporary matters. But as a treatment of the Augustan age, it is primarily allegorical.

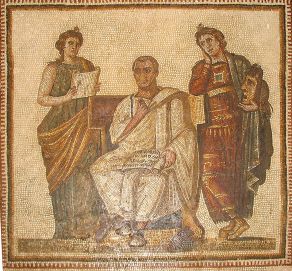

Late Antique Depiction of Virgil. (Commons)

Augustan Ideology, Propaganda, and Poetry

We can see a direct contact between Virgil, Horace and possibly Propertius and the Augustan regime through Maecenas, Augustus’ close friend, who acted as patron. But the link between the wishes of the patron and the creative work is not clear.

If we think of propaganda in its modern sense, that is as politically contentious messages propagated by representatives of the regime, then Augustan poetry cannot fit that model. Nevertheless, it is clear that Virgil and Horace especially were often supportive of the regime and its values.

The notion of propaganda tends to suggest that a regime has a particular ideological perspective that is then transmitted through the work of art. Some modern regimes have had coherent and philosophically worked out bodies of belief. Ancient regimes were not ideological in such a way. A political group might have a set of political beliefs which we could describe as an ideology, but regimes were not prone to make coherent statements of their ideological positions.

As historians, we reconstruct what the regime thought through the occasional statement that is transmitted to us, but mostly from what the regime did. The poets contribute to that reconstruction. Although much of the poetry concerns issues which we might regard as private, the Augustan regime also concerned itself with private affairs. Consequently, If a poet wrote about ‘his girl’, that was a political text because of Augustan legislation on sexual behaviour. If a poet wrote on the foundation of Rome, the text had added resonances because Augustus was posing as refounder of the city.

What the poetry gives us is the intellectual climate of the Augustan period. The Augustan period was one of change, paradox, debate and doubt. It should come as no surprise then the poets of the period do not display a consensus on Augustus and those values we identify as Augustan. It should not come as a surprise that we find elements of criticism in poetry that is generally favourable or elements of praise in poetry that is generally hostile.

We can thus read the poetry as commentary on the events and ideas of the day not the voicing of political factions.

Augustus Moral Reforms Maecenas and Terentia Ovid and the Arts of Love The New Age