Caesar’s Dictatorship

Caesar won the war that began when he crossed the Rubicon. In spite of the long build-up to the war, the Pompeians had not been ready to face Caesar in Italy. They retreated and gathered forces in Spain and Greece. Although Caesar controlled Italy, his position was difficult. It seems likely that he was soon outnumbered by the Pompeian legions. Pompey’s control of the East and Spain also meant that he had greater resources at his disposal. Caesar, typically, took the initiative.

The first great battle was in Spain at Ilerda, fought through late May and June 49. The battle was a complex serious of manoeuvres through which Caesar went from being isolated and without food, his legions divided by a river in flood, to forcing a larger Pompeian army to surrender through lack of water.

Buoyed by the victory, Caesar moved on to Greece, where he faced Pompey himself. After defeat at Dyrrachium, Caesar and Pompey met again at Pharsalus on 9th August, 48. It was a decisive victory for Caesar.

Pompey retreated to the East. But the rulers of the East could see how the war was going and were anxious not to make an enemy of the future ruler of the Roman world. Pompey went to Egypt where he was murdered on the orders of Ptolemy XIII.

It did Ptolemy no good. He was in dispute with his sister, Cleopatra.

Cleopatra VII (Photo: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro) (Altes Museum, Berlin) (Commons)

Caesar was anxious not to be seen to support treachery and it turned out that Cleopatra had considerable charms that made his alliance with her pleasurable (see here for portraits in the Altes Museum, Berlin).

The death of Pompey did not bring an end to the Pompeian cause. Cato (the younger) had left Pompey after the battle of Pharsalus. He went to Africa to lead resistance from there. The Pompeians were defeated at the Battle of Thapsus in 46 BC. Cato committed suicide, announcing that he could not live in a Caesarian world. This cemented his reputation as a man of principle and made him famous in antiquity as a model of resistance to tyranny (see Plutarch’s Life of Cato the Younger). His example was used by later opponents of emperors.

Caesar forgave his enemies and invited them to return to Rome. He thereby displayed clementia (mercy), a valued if somewhat regal quality. In Caesar’s view, the war had been a terrible misunderstanding, sprung on the Roman people by a tiny minority of his personal enemies. There was no major ideological divide. There was no need for revenge. All could come together and make peace.

His surviving enemies were in his debt because they had been forgiven. One assumes that they were glad to return to Rome. This does not mean that they were reconciled to the new regime.

Caesar in Rome

Caesar’s constitutional position was messy. He was consul in 48, 46, 45, and 44 BC. He also took the title of Dictator.

This last was a constitutional office. It was originally an emergency power and granted for a specific task, such as holding elections or facing a military crisis, when the normal magisterial system had somehow failed. Sulla had used the dictatorship as the constitutional basis of his power. Caesar’s consulships gave him control over the political and military machinery of the Roman state. But having held dictatorships for short periods (Plutarch, Julius Caesar 37; 51; 57), he seems to have decided to extend his dictatorship, perhaps for life. This seems to have been one of several honours that elevated Caesar above his fellow senators (Suetonius, Caesar 76).

Caesar’s honours offended many of the basic principles of Republican government. The key question becomes why he did these things. The conventional reason is that he was aiming at monarchy, but why would Caesar, who had such a level of political control, want to be monarch?

Vanity and ambition are obvious and easy answers. This was a man who had taken the young Egyptian queen as his lover and installed he in a villa on the outskirts of Rome. He also claimed descent from Venus and to reinforce that claim built a Temple to Venus Genetrix (Venus the Mother) in a new Forum that he was building in the centre of the city. But the exercise of clementia after the war suggests that Caesar was anxious to return to the consensus on which Republican government was based.

Perhaps the most obvious explanation was that consensus was impossible while Caesar was the dominant force. The question of who ruled still animated Roman politics. If the Republic was identified with the rule of senators, then it could not countenance Caesarian domination. Caesar’s presence was a paradox in a Republican system. One guesses that this paradox caused friction and Caesar responded by further elevating himself, emphasising his exceptionalism.

By 44 BC, Caesar had a new plan. He was to go off to the East and conquer the Parthians. Victory in the East would mean not only was he the rival of Pompey, but also of Alexander the Great. Surely that would be enough to quieten the dissent? His last meeting of the senate before heading to Macedonia to join his legions was planned for March 15th, the Ides of March. It was there and then that was murdered.

Gerome, The Assassination of Julius Caesar (The Walters Art Gallery)

The conspirators were a political faction led by Junius Brutus and Cassius Longinus. It is not hard to discern their ideology. They wished to restore the Republic.

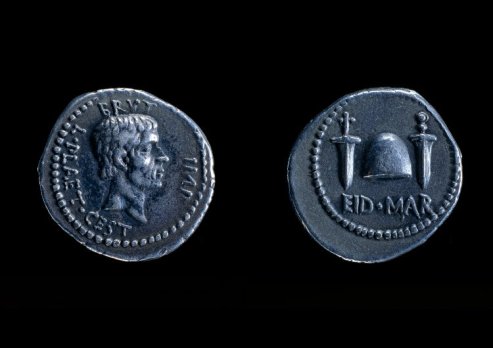

Coin issued by Brutus (pictured left). The image shows the cap of liberty as worn by freed slaves and the daggers by which liberty was obtained. (British Museum)

They presented Caesar’s power as a tyranny. Their action was to free Rome from the rule of a tyrant.

The conspiracy was large in part because the conspirators wished to control what happened after Caesar. A powerful group of senators would surely be able to assert their authority and show the Roman people (and they might have assumed that the Roman populace would have be grateful to be rid of the tyrant), who ruled.

They were wrong.

Caesar on the Rubicon The Triumvirs After the Assassination